Finally! I’m so excited to present my second post on genitalia! Thank you all again for your patience while I worked on life things and neglected this blog. I’m trying to get more organized and better at juggling real life with my online commitments. But for now, I’m going to continue with the theme of external human sexual anatomy. This entry will focus on the vulva’s counterpart: the penis. Whereas the vulva is composed of many different organs housed within the same space, the penis is one large organ with a few different sections. This difference aside, these two genitals are strikingly similar. They both have a urethra and various internal organs associated with external markers. They both have pubic hair. They’re both symmetrical, and they are both formed from the same endometrial layers in the fetus. You may recognize a lot of language in this post from the previous post, especially when it comes to my writings on the clitoris. That’s because (wait for it), the penis, when you get down to it, is basically an enlarged, external clitoris.

The Penis

First things first: there are generally two “types” of penises in the world: circumcised, and uncircumcised. Categorizing penises into these two types isn’t quite fair, because all penises are technically created uncircumcised, but might become circumcised later on in life (really mostly immediately to a few days after birth). The circumcision process is usually performed by a doctor (or a mohel, depending on your religion and religious beliefs). It’s a fairly simple procedure: the person performing the circumcision makes a single cut on the foreskin of the penis, rolls it back past the glans, and snips it off.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), about one-third of the penises in the world are circumcised. However, circumcision rates vary country by country, with the procedure being more common in Israel, the Muslim World, the U.S., and some sections of Southeast Asia and Africa.

Depending on whom you ask circumcision is either a harmless and beneficial medical procedure or a disastrous one. Organizations such as Intact America and the Circumcision Information and Resource Pages (CIRP) argue that circumcision adversely affects people with penises because it takes away a natural skin layer designed to protect the penis and also detracts from sexual pleasure. People in favor of circumcision counter that removing the penis’s foreskin has been proven to lower the risk of contracting HIV/AIDS in high risk populations and makes it easier to clean the penis and thus lowers the risk of urinary tract infections (UTIs) and other medical complications. Groups on both sides of the argument have very strong opinions about the issue, and they’ll both insist that one type of penis is better than the other. But here’s the thing: the benefits that each side lists are pretty minimal. Keeping the glans of the penis clean is easy even if you’re uncircumcised – you just have to remember to pull back the penis’s foreskin to wash the glans. If you don’t live in a part of the world considered a “high risk” area for HIV/AIDS, circumcision won’t really minimize your chances of contracting it. And as far as I know, circumcised people are perfectly capable of finding sexual activity pleasurable. In fact, some uncircumcised people complain that they think they are too sensitive, to the point where they find sexual acts without a condom (oral sex, intercourse) painful, especially when the foreskin that usually protects the very sensitive glans naturally rolls back. This is all to say that there’s really no way of proving that a circumcised penis is better than an uncircumcised one or vice versa. They’re just a little different.

But…what is a foreskin? The foreskin (also called the prepuce) of the penis isn’t exactly what it sounds like: it’s not entirely made of skin, although it looks like it. The foreskin actually has two layers: an outer one and an inner one (see below). The outer layer is a continuation of the skin on the shaft of the penis, while the inner layer is made of mucocutaneous tissue (meaning that it’s actually a mucous membrane that secretes, well, mucous. It keeps the glans moist). Near the tip of the foreskin, this membrane transitions to the skin of the external membrane.

The foreskin is enervated and vascular, which means that it has both nerve endings and blood vessels inside of it. It’s not just a dead piece of skin covering some of the penis: it’s alive! And get this: it’s completely analogous to the clitoral hood – they’re made of exactly the same things! They also both serve the function of covering an organ’s extremely sensitive glans. Except while the clitoral hood covers the glans of the clitoris, the foreskin covers the glans of the penis.

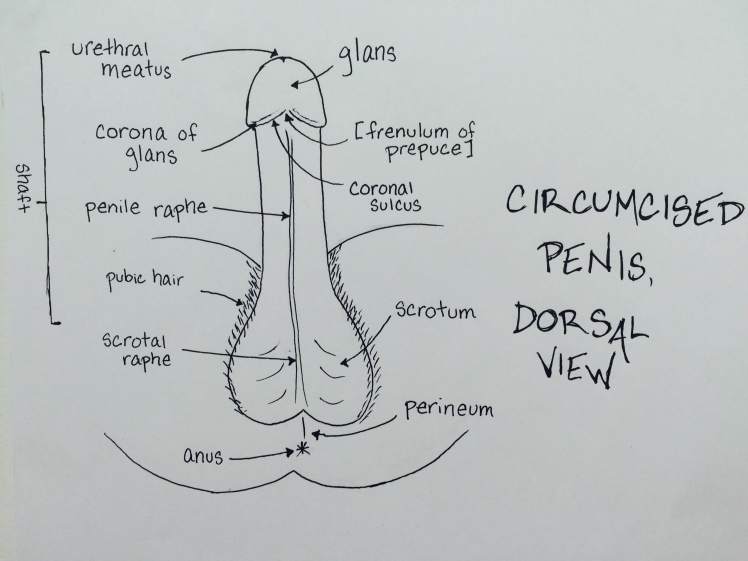

You can interpret the above diagram as showing either a circumcised penis or an uncircumcised penis with the foreskin rolled back. I’ve chosen to remove the foreskin in this drawing because it covers a lot of landmarks on the penis that are important to mention and talk about.

People often think of the penis as having two parts: the shaft and the head. In this case, the shaft of the penis refers to everything from the base of the penis to the coronal sulcus. However, at other times, people might use the word shaft to differentiate the penis from the scrotum, at which point the term shaft will include the head/glans of the penis. In this diagram, I have shown the shaft of the penis as including the head.

Glans – the glans of the penis (also sometimes called the head of the penis), as you’ve probably figured out, is analogous to the glans of the clitoris. It contains a huge amount of sensory nerve endings and is thus considered the most sensitive part of the penis (although this won’t be true for all folks – keep reading). You’ll also notice that the glans is slightly wider than the rest of the penis (this is why quick dick sketches look a lot like mushrooms). Some evolutionary scientists have suggested that the glans of the penis evolved to look like this because that particular bell-like shape can function as a scoop and remove other peoples’ semen from a vagina. The significance being that if you wanted to reproduce in an age where monogamy wasn’t really the norm (read: probably the majority of human existence), you needed to have a penis that was extraordinarily good at preventing any sperm but your own from reaching the uterus of your chosen partner(s). Thus, people with a glans that scooped out competing sperm passed on their scooper-genes to the next generation.

This theory of semen displacement was actually the subject of an experiment performed by a group of evolutionary behaviorists at the State University of New York at Albany, who found that penises with a “ridged glans” were capable of scooping out 91% of previously deposited semen in a vagina, whereas a penis without a ridge would only remove 45%. (If you’re curious about their exact experimental procedure, see Mary Roach’s Bonk: The Curious Coupling of Science and Sex, pgs. 126-127).

Urethral Meatus – just like people with vulvas, people with penises have a urethra, and they pee from it. It is surrounded by the periurethral glans, which can provide sensations of pleasure. Unlike in the vulva, however, the urethral meatus of the penis can also ejaculate semen, a substance consisting of sperm as well as a few other fluids. However, only one substance can exit the urethra at a time: it’s either going to be semen or pee. The body actually has a mechanism to stop people from peeing when the penis is in a state where it’s likely to ejaculate semen: when a penis becomes erect, a valve near the bladder called the internal urethral sphincter closes, making it extremely difficult to pee. This isn’t to say that it’s impossible to pee with an erection, but it’s definitely (no pun intended) harder.

Corona of Glans – the corona is the protruding part of the glans that gives it its scooping ability. The corona also sometimes has some small bumps on it called Hirsuties coronae glandis, or, for those of us who like alliteration, pearly penile papules. They’re perfectly harmless and normal. The coronal sulcus is the part of the penis directly underneath the corona. In Latin, sulcus means furrow. In anatomical language, it’s usually used to refer to a groove or a fissure.

Frenulum – the frenulum connects the foreskin to the shaft of the penis. Uncircumcised penises will always have a frenulum; circumcised people might have it, or it might have been removed during circumcision. The frenulum is recognized as an erogenous zone.

Penile Raphe – the penile raphe is a thin line that runs down the dorsal side of the penis and continues down the genitals, to where it becomes the scrotal raphe. It’s this part of the penis that reminds us of the organ’s symmetry and how it develops in the womb: during embryological development, the penis grows outward and then bends around to fuse in the center. The entire body actually does this; it’s just cool that it’s so visible on the genitals.

Pubic Hair – this is still a mystery to me: what is the function of pubic hair around a penis? While the vulva gains protection from external elements entering the labia, the penis is entirely external. It’s possible that the hair provides padding or perhaps warmth? Either way, all people have pubic hair. Pubic hair may stay on the base of the penis, or advance up the shaft. At least part of the scrotum usually also has pubic hair.

Scrotum – the scrotum is a sack of thick skin that houses the testes, which produce sperm. The scrotum is a really cool body part because it’s composed of a fair amount of smooth muscle that can raise or lower the testes depending on outside temperature. The testes need to hang a little bit away from the body because sperm develop and survive best at 35 degrees Centigrade (or 95 degrees Fahrenheit), which is below the usual human body temperature of 37˚C/98.6˚F. So if it’s hot out, the scrotum will lower the testes and allow them to hang away from the body’s natural heat, while colder temperatures will cause the smooth muscle to contract and pull the testes closer to their owner’s body heat so the poor sperm don’t freeze. It’s also worth noting that the scrotum develops from the same section of embryological tissue that forms the labia majora in people with vulvas.

Perineum – again I refer to the area of skin between the penis/scrotum and anus, which is an erogenous zone.

In the above list, I have tried to give a summary of the landmarks associated with the penis. As always, this diagram is only a representation of a penis and not at all supposed to indicate what a penis should or should not look like. Like vulvas, each penis is beautiful and unique and each will have its own idiosyncrasies. As always, I encourage readers to explore on their own to learn more about the penis and its various components. Wikipedia is your friend, especially if you’re just looking for simple definitions of words or pictures; I would advise avoiding the various “community boards” that I found online during my research, where anyone can ask or answer a question. Beware of false information!

Erection

There’s one other thing that any blog post on penises must cover: erections. We’ll get to ejaculation later, because it’s mostly an internal process, but erection is so obviously an external event that it deserves to be reviewed here.

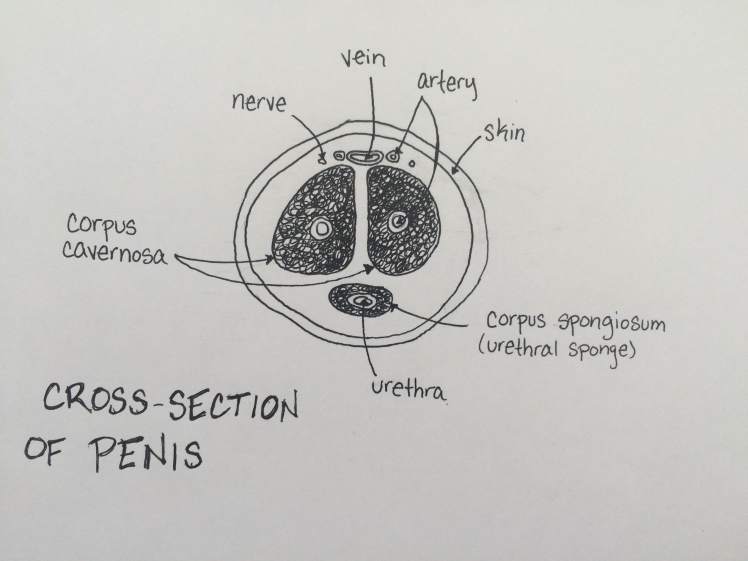

The penis is made up of many things, but the vast majority of it is made up of erectile tissue. There are two main types of erectile tissue: the corpus cavernosa and the corpus spongiosum. Most of the penis consists of the corpus cavernosa; the corpus spongiosum surrounds the urethra (see below). If this all sounds familiar, it should. The erectile tissue making up the shaft of the clitoris is called the corpus cavernosum, and the corpus spongiosum is basically the same as the urethral sponge in the clitoris. Like I said, penises are basically enlarged clitorises.

There are also nerve endings, veins, and arteries in the penis, all of which play a part in the process of erection. Erection begins when the involuntary nervous system receives some kind of signal. Intuitively, we assume that this signal must be sexual in some way – but no, erections happen in all types of non-sexual situations as well. Like while giving a presentation in school or zoning out on the bus. My friends with penises inform me that these types of erections are called “No Apparent Reason Boners” or “APRBs”. Erection-causing signals also come in sleep: the human body is programmed to have erections during the REM cycle. If you sleep, you get erections. Both clitoral and penile.

Sexual or not, when the involuntary nervous system receives that signal, the body releases a vasodilator called nitric oxide, which causes the arteries of the penis to dilate. More blood than usual flows into these enlarged arteries, thus filling the erectile tissue with blood and, viola, the penis becomes erect. And then it stays erect, thanks to certain penile muscles that constrict the veins that would normally allow the blood entering the penis to flow out of it. And there you have it: a penis becomes erect when blood enters it and then can’t leave. This results in the penis getting a lot harder and straighter and, in many cases, larger.

Penises can change a lot when they’re erect. In my opinion (and feel free to disagree with me), a flaccid penis is a flaccid penis – aside from color and size, it’s hard to tell them apart. But erect, penises will take on personalities. They’ll curve in different ways and directions – some will bend upwards, others downwards, others to the side. Some will grow dramatically, some hardly at all (if you’ve ever heard people talk about a person being a “shower” rather than a “grower” or vice versa, this is what they’re referring to. Probably). You’ll often be able to more clearly see veins in an erect penis…or not. Uncircumcised folks may notice that their foreskin naturally rolls back when they become erect – for others, this won’t be the case.

All this is to say that penises will always be different – more noticeably so when they’re erect! They’re all different lengths and girths and colors when they’re flaccid, and this will change when they become erect and maybe some will be girthier and longer than the one that seemed larger flaccid. Penises are capable of such flux: it’s pretty amazing.

On Size

For some unfathomable reason, penises and penis size seem to have become, at least in American culture, a measure of a person’s worth, especially if they are male-identified. I hope that we’ve gotten past the phase where people were explicitly told that bigger is better, but there’s still a lot of subliminal messaging that implies that larger penises are more manly, better at pleasing partners, and ultimately determine how good of a person you are. It certainly doesn’t help that most porn stars seem to be sporting huge elephant trunks between their legs, and as most people will see far more erect penises of porn stars than of non-porn stars, it’s easy to believe that penises that aren’t 10 inches long are somehow inferior.

If you want the down and dirty, here it is: most penises, when erect, measure between 4.6 and 6.2 inches. That’s about an inch and a half of variation between the vast majority (about 90%) of penises. According a review in the Journal of Sexual Medicine, which referred to data from eight different penis-size studies, the average length of a flaccid penis is 3.5 inches, with the average length of an erect penis being 5 inches. It’s also worth noting that out of all of the primates on the planet, humans have the thickest and longest penises. And that’s not even adjusting for body size.

If you’re curious about the size of your penis, the correct way to measure, according to the Guide to Getting it On (one of my favorite informational guides of all time) is to measure from the pubic bone to the tip of the glans. This is, of course, far easier to do when erect. An associate of mine has also noted that most people measure their penises in “dick inches,” meaning that they add a half-inch to an inch to their final measurement, so feel free to do that too. Do note that measuring in dick inches will make my average penis size statistics above seem a bit small, but that’s okay: researchers generally don’t add an inch when they measure a penis. In fact, self-reported penis length varies from scientifically-recorded penis length by about an inch. Meaning that, if you really want to know the exact size of your penis, ask a scientist (or just an unbiased party) to measure it for you.

Here’s the other thing I don’t get about penis size myths: why is it that only penis size is said to determine the quality of the sex one has? This standard doesn’t exist for people with vulvas. No one has ever told me that I will be lousy in bed because my vagina is too short, or because my labia are the wrong width. What is it about penises that make them so special? The answer, of course, is that there isn’t anything. Penis size doesn’t determine the quality of one’s sexual life any more than the length of a person’s vagina or the number of fingers on their hands. The real issue at play here is sexism targeted at penis-owning individuals. The idea that penis size can determine personal worth puts unfair pressure on people with penises. It results in body-image problems and insecurity. It can hurt self-esteem. Sexism affects everyone, not just female-bodied-or-identified-people. And myths about penis size and their possibly detrimental effects on an individual demonstrate how sexism also adversely impacts male-bodied-or-identified-people.

I’ll share an obvious secret: if you want to have good sex, stop worrying so much about the size of your penis or your partner’s penis (if neither partner has a penis, stop worrying about other physical things you might be worrying about) and start worrying about communication. Because you can have the largest penis in the world, but if you don’t communicate with your partner(s) about what you and they enjoy, the sex won’t be very good. I’ll write this sentence again and again in this blog, because it’s true: communication is the key to good sex. It’s not about the size of your penis or your labia, the color of your genitals, your lack or abundance of pubic hair – it’s about talking to each other and knowing how to express what you enjoy and what you don’t. If you are able to successfully communicate with your partner, you will have amazing, fantastic, satisfying sex. And believe me, I’m going to cover all the ways that you can have amazing, fantastic, satisfying sex soon. But not yet. Because we’re still on anatomy, and next time I want to cover all the weird and wonderful stuff associated with sex inside the human body.

References

Circumcision Information and Resource Pages. “Anatomy of the Penis, Mechanics of Intercourse.” 2005.

Fulbright, Yvonne K. The Hot Guide to Safer Sex. Alameda, CA: Hunter House Publishers, 2003.

Joannides, Paul. Guide to Getting it On, 8th ed. Waldport, OR: Goofy Foot Press, 2015.

Moen, Erika. “Foreskin Funsies.” Oh Joy, Sex Toy. 2015.

Roach, Mary. Bonk: The Curious Coupling of Science and Sex. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2008.

Ryan, Christopher and Cacilda Jetha. Sex at Dawn: How We Mate, Why We Stray, and What It Means for Modern Relationships. New York: Harper Perennial, 2011.

Shultz, David. “How Big is the Average Penis?” American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2015.

Wikipedia: Corona, Glans, Frenulum, Penile Raphe

Reblogged this on Recked with Finn West and commented:

A fascinating insight into male genitalia.

Finn

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Gay Guide To Cambodia and commented:

Need to know

LikeLike

One of the very few that mention the frenulum. Good job! BTW did you know the frenulum has pressure sensitive nerve ending found no where else in the body?

LikeLike